The concepts of digital accessibility are becoming known and understood by more people every day. As this knowledge gets implemented by a growing number of individuals and companies, some people who were historically excluded from equal access to online information can now consume and contribute to digital experiences more fully — when those experiences are built with their needs and methods of interacting with the material in mind. One too-often-overlooked area of web accessibility is creating content that may be easier for people with dyslexia to understand.

Todo tipo de información sobre accesibilidad en la Web: errores de accesibilidad, ejemplos de páginas inaccesibles, noticias, software, hardware, productos de apoyo, consejos, pautas y guías de accesibilidad, WAI, WCAG, Norma EN 301 549, legislación, etc.

Buscador

viernes, 5 de julio de 2019

Cómo crear contenido accesible para las personas con dislexia

En How to Create Accessible Content and Designs for People with Dyslexia se proporcionan algunos consejos para crear contenido accesible para las personas con dislexia:

miércoles, 3 de julio de 2019

Uso de "persona profiles" para testear la accesibilidad

En Using persona profiles to test accessibility se explica:

In 2017, the Accessibility Team at the Government Digital Service (GDS) created accessibility personas to highlight common barriers faced by people with particular conditions and provide tips on how to design for them.

These user profiles are used by teams such as user researchers and developers to create services that are accessible to all. For instance, there is a persona for Pawel, a user with Asperger’s and one for Simone, a dyslexic user.

While personas can be a great tool by themselves, we wanted to let people experience the web as that user. So, we created login profiles for each persona. These login profiles simulate the user’s condition and the tools he or she may be using to help with that condition.

After testing on different devices, we found that Chromebooks were the most successful device on which to use our accessibility persona logins. We explain why in more detail further down.

lunes, 1 de julio de 2019

La importancia de resaltar el foco

En Focusing on Focus Styles se explica la importancia de resaltar el foco en las páginas web:

Y se explica el uso de :focus, :focus-within y :focus-visible.

Not everyone uses a mouse to browse the internet. If you’re reading this post on a smartphone, this is obvious! What’s also worth pointing out is that there are other forms of input that people use to get things done. With these forms of input comes the need for focus styles.

People are complicated. We don’t necessarily perform the same behaviors consistently, nor do we always make decisions that make sense from an outsider’s perspective. Sometimes we even do something just to… do something. We get bored easily: tinkering, poking, and prodding things to customize them to better suit our needs, regardless of their original intent.

People are also mortal. We can get sick and injured. Sometimes both at once. Sometimes it’s for a little while, sometimes it’s permanent. Regardless, it means that sometimes we’re unable to do things we want or need to do in the way we’re used to.

People also live in the world. Sometimes we’re put into an environment where external factors conspire to prevent us from doing something the way that we’re accustomed to doing it. Ever been stuck at your parents’ house during the holidays and had to use their ancient-yet-still-serviceable desktop computer? It’s like that.

Y se explica el uso de :focus, :focus-within y :focus-visible.

viernes, 28 de junio de 2019

Libro "Web Accessibility - A Foundation for Research"

El libro Web Accessibility - A Foundation for Research se acaba de publicar. El contenido del libro es:

Front Matter

Pages i-xxiii

Understanding Disabilities

Front Matter

Pages 1-1

Visual Disabilities

Armando Barreto, Scott Hollier

Pages 3-17

Physical Disabilities

Shari Trewin

Pages 19-33

Deafness and Hearing Loss

Raja Kushalnagar

Pages 35-47

Cognitive and Learning Disabilities

Lisa Seeman, Clayton Lewis

Pages 49-58

Situationally-Induced Impairments and Disabilities

Jacob O. Wobbrock

Pages 59-92

Ageing and Older Adults

Sri Kurniawan, Andrew Arch, Sean-Ryan Smith

Pages 93-119

Speech and Language

Abi Roper, Stephanie Wilson, Timothy Neate, Jane Marshall

Pages 121-131

Conducting Research

Front Matter

Pages 133-133

Inclusive Writing

Tom Babinszki, Anna Cavender, Michael Gower, Jeffery Hoehl, Darcy Lima, Erich Manser et al.

Pages 135-152

Working With Participants

Christopher Power, Helen Petrie

Pages 153-168

Working with Companies, Charities and Governmental Organisations

Andrew Arch, Lisa Seeman, Sarah Pulis, Glenda Sims

Pages 169-183

End-User Evaluations

Sukru Eraslan, Chris Bailey

Pages 185-210

Reproducible and Sustainable Research Software

Caroline Jay, Robert Haines

Pages 211-221

Society and Standards

Front Matter

Pages 223-223

Standards, Guidelines, and Trends

Shadi Abou-Zahra, Judy Brewer

Pages 225-246

Web Accessibility Policy and Law

Jonathan Lazar

Pages 247-261

Tackling the Inaccessibility of Websites in Postsecondary Education

Jane Seale, Sheryl Burgstahler, Björn Fisseler

Pages 263-279

Policy and Standards on Web Accessibility for Cognitive and Learning Disabilities

Clayton Lewis, Lisa Seeman

Pages 281-299

Inclusion

Cynthia C. Shelly

Pages 301-313

Technical Foundations

Front Matter

Pages 315-315

Assistive Technologies

Hugo Nicolau, Kyle Montague

Pages 317-335

Documents and Publications

Vivienne Conway, Amanda Mace

Pages 337-355

Inclusively Designed Authoring Tools

Jutta Treviranus, Jan Richards, Colin Clark

Pages 357-372

Dynamic Web Content

Renata Pontin de Mattos Fortes, Humberto Lidio Antonelli, Willian Massami Watanabe

Pages 373-395

Scientific Documents

Volker Sorge, Dragan Ahmetovic, Cristian Bernareggi, John Gardner

Pages 397-415

Mathematics and Statistics

Neil Soiffer, Steve Noble

Pages 417-443

Usability, Universal Usability, and Design Patterns

David Sloan, Sarah Horton

Pages 445-460

Multimedia Accessibility

Carlos Duarte, Manuel J. Fonseca

Pages 461-475

Techniques and Tools

Front Matter

Pages 477-477

Tools for Web Accessibility Evaluation

Julio Abascal, Myriam Arrue, Xabier Valencia

Pages 479-503

Automatic Web Accessibility Metrics

Giorgio Brajnik, Markel Vigo

Pages 505-521

Tools and Applications for Cognitive Accessibility

K. Miesenberger, C. Edler, P. Heumader, A. Petz

Pages 523-546

User Interface Adaptation for Accessibility

Sergio Firmenich, Alejandra Garrido, Fabio Paternò, Gustavo Rossi

Pages 547-568

Transcoding

Chieko Asakawa, Hironobu Takagi, Kentarou Fukuda

Pages 569-602

Technologies for Dyslexia

Maria Rauschenberger, Ricardo Baeza–Yates, Luz Rello

Pages 603-627

Alternative Nonvisual Web Browsing Techniques

I. V. Ramakrishnan, Vikas Ashok, Syed Masum Billah

Pages 629-649

Education and STEM on the Web

Barbara Leporini, Marina Buzzi

Pages 651-674

Ubiquitous Web Accessibility

Front Matter

Pages 675-675

Wayfinding

Daisuke Sato, Hironobu Takagi, Chieko Asakawa

Pages 677-700

Wearables

Shaun K. Kane

Pages 701-714

Tangible Interfaces

Mark S. Baldwin, Rushil Khurana, Duncan McIsaac, Yuqian Sun, Tracy Tran, Xiaoyi Zhang et al.

Pages 715-735

Mobile Web

Tiago Guerreiro, Luís Carriço, André Rodrigues

Pages 737-754

Fabrication, 3D Printing, and Making

Amy Hurst

Pages 755-776

Internet of Things: An Opportunity for Advancing Universal Access

Federica Cena, Amon Rapp, Ilaria Torre

Pages 777-790

Futurama

Yeliz Yesilada, Simon Harper

Pages 791-803

Back Matter

Pages 805-807

miércoles, 26 de junio de 2019

La importancia de nombrar las cosas para mejorar la accesibilidad web

En Naming things to improve accessibility se explica:

One thing you can do to improve the accessibility of your work is to always ensure things have accessible names. Unique and useful names, ideally, so that they can be used for navigation. In this post I’ll explain how browsers decide on the names for links, form fields, tables and form groups.

Accessibility Tree

When a user accesses your site, the server will send markup to the browser. This gets turned into trees. We’re probably all familiar with the DOM tree, a live representation of your markup, with all nodes turned into objects that we can read properties of and perform all sorts of functions on.

What many people don’t know, is that there is a second structure that the browser can generate: the accessibility tree. It is based off the DOM tree, and contains all meta information relation related to accessibility: roles, names and properties. Another way to say it: the accessibility tree is how your page gets exposed to assistive technologies.

One thing you can do to improve the accessibility of your work is to always ensure things have accessible names. Unique and useful names, ideally, so that they can be used for navigation. In this post I’ll explain how browsers decide on the names for links, form fields, tables and form groups.

Accessibility Tree

When a user accesses your site, the server will send markup to the browser. This gets turned into trees. We’re probably all familiar with the DOM tree, a live representation of your markup, with all nodes turned into objects that we can read properties of and perform all sorts of functions on.

What many people don’t know, is that there is a second structure that the browser can generate: the accessibility tree. It is based off the DOM tree, and contains all meta information relation related to accessibility: roles, names and properties. Another way to say it: the accessibility tree is how your page gets exposed to assistive technologies.

lunes, 24 de junio de 2019

Reproductor de vídeo que permite seleccionar capítulos

En Building Interactive HTML5 Videos podemos encontrar un reproductor multimedia que permite seleccionar los capítulos del vídeo, para saltar fácilmente entre secciones de un vídeo.

Y en Adding captions and subtitles to HTML5 video se explica cómo gestionar los subtítulos desde JavaScript.

Y en Adding captions and subtitles to HTML5 video se explica cómo gestionar los subtítulos desde JavaScript.

viernes, 21 de junio de 2019

Guía de creación de subtítulos de la BBC

Subtitles are primarily intended to serve viewers with loss of hearing, but they are used by a wide range of people: around 10% of broadcast viewers use subtitles regularly, increasing to 35% for some online content. The majority of these viewers are not hard of hearing.

This document describes 'closed' subtitles only, also known as 'closed captions'. Typically delivered as a separate file, closed subtitles can be switched off by the user and are not 'burnt in' to the image.

The Subtitle Guidelines describe best practice for authoring subtitles and provide instructions for making subtitle files for the BBC. This document brings together documents previously published by Ofcom and the BBC and is intended to serve as the basis for all subtitle work across the BBC: prepared and live, online and broadcast, internal and supplied.

martes, 18 de junio de 2019

El papel de los traductores en la inclusión de las personas con discapacidad

La semana pasada asistí a las III Jornadas INCLUTRAD de Accesibilidad, Discapacidad y Traducción, organizadas por la Universidad Pablo de Olavide en Sevilla

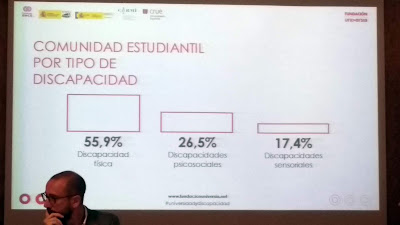

Ramón Rodríguez, director de proyectos globales de la Fundación Universia presentó el IV Estudio Universidad y Discapacidad. Según este estudio, un 1,5% de la población universitaria presenta una discapacidad.

El tipo de discapacidad más frecuente es la física con un 55,9%, seguida de las discapacidades psicosociales con un 26,5% y las discapacidades sensoriales con un 17,4%.

Las jornadas se retransmitieron en directo por Internet. En todo momento hubo interpretación a la lengua de signos española.

También se utilizó el sistema Webcaptioner para ofrecer transcripción en vivo.

Más información:

Ramón Rodríguez, director de proyectos globales de la Fundación Universia presentó el IV Estudio Universidad y Discapacidad. Según este estudio, un 1,5% de la población universitaria presenta una discapacidad.

El tipo de discapacidad más frecuente es la física con un 55,9%, seguida de las discapacidades psicosociales con un 26,5% y las discapacidades sensoriales con un 17,4%.

Las jornadas se retransmitieron en directo por Internet. En todo momento hubo interpretación a la lengua de signos española.

También se utilizó el sistema Webcaptioner para ofrecer transcripción en vivo.

Más información:

viernes, 14 de junio de 2019

La primera regla de ARIA

Conviene recordar la primera regla de WAI-ARIA (2.1 First Rule of ARIA Use):

If you can use a native HTML element [HTML51] or attribute with the semantics and behavior you require already built in, instead of re-purposing an element and adding an ARIA role, state or property to make it accessible, then do so.

Under what circumstances may this not be possible?

- If the feature is available in HTML [HTML51] but it is not implemented or it is implemented, but accessibility support is not.

- If the visual design constraints rule out the use of a particular native element, because the element cannot be styled as required.

- If the feature is not currently available in HTML.

miércoles, 12 de junio de 2019

III Jornadas Inclutrad de Accesibilidad, Discapacidad y Traducción (INCLUTAD 2019)

La Universidad Pablo de Olavide (UPO) de Sevilla organiza las III Jornadas Inclutrad de Accesibilidad, Discapacidad y Traducción (INCLUTAD 2019) los días 13 y 14 de junio de 2019.

El jueves 13, a las 18 horas, impartiré la conferencia "La accesibilidad de los sitios web como recurso fundamental de información y formación".

En EL PRESIDENTE DEL CERMI ANDALUCÍA INTERVIENE ESTE JUEVES EN SEVILLA EN LAS III JORNADAS INCLUTRAD SOBRE ACCESIBILIDAD, DISCAPACIDAD Y TRADUCCIÓN y en Cermi y la Universidad Pablo de Olavide organizan unas jornadas sobre accesibilidad, discapacidad y traducción podemos leer más sobre este evento.

El jueves 13, a las 18 horas, impartiré la conferencia "La accesibilidad de los sitios web como recurso fundamental de información y formación".

En EL PRESIDENTE DEL CERMI ANDALUCÍA INTERVIENE ESTE JUEVES EN SEVILLA EN LAS III JORNADAS INCLUTRAD SOBRE ACCESIBILIDAD, DISCAPACIDAD Y TRADUCCIÓN y en Cermi y la Universidad Pablo de Olavide organizan unas jornadas sobre accesibilidad, discapacidad y traducción podemos leer más sobre este evento.

lunes, 10 de junio de 2019

Requisitos de WCAG sobre el contraste y el color

En Understanding WCAG 2 Contrast and Color Requirements, se explican los requisitos de WCAG relacionados con el contraste y el color.

viernes, 7 de junio de 2019

No hay que confiar ciegamente en las herramientas automáticas de evaluación de la accesibilidad web

En Automated Lies, with one line of code se da una buena explicación de los problemas o de las cosas que no hacen las herramientas automáticas de evaluación de la accesibilidad web:

It should be universally understood that automated testing tools cannot offer complete test coverage for all possible accessibility issues on the web. Therefore it stands to reason that if you cannot automatically find all your site’s accessibility issues, you certainly cannot automatically fix all of them, either. This is extraordinarily simple logic. In fact, automatically fixing issues is even less likely to be successful than finding them. This fact is demonstrated within Mallet. While Mallet is extremely good at finding & fixing some issues, it is still limited to around 2-dozen types of ‘fixes’ that work on their own without any configuration. The remainder of Mallet’s fixes require some level of configuration. To put this into perspective, Tenon.io has approximately 200 accessibility tests that look for around 2500 different failure conditions. In other words, we can easily find at least 10x as many issues as we can reliably fix, because fixing the issues requires far more knowledge about the user interface than an automated tool has.Y también dice:

As always, it is important to remind the reader that there are limits to what can be discovered with automatic testing. It stands to reason that if you cannot automatically test for something you definitely cannot fix it, either.

- Captions/ transcripts for audio-only content or audio content in videos.

- Audio description for video content

- Content that relies on sensory characteristics to understand

- Audio control

- Keyboard trap

- Pause, Stop, Hide

- Error prevention and error handling

- Effective focus management

The above is only a subset of the many things in web accessibility that cannot be accurately tested via automated means. Many of them are hugely impactful for people with disabilities.

- Reading level

miércoles, 5 de junio de 2019

Cómo construir un sitio web que sea 100% accesible y que realmente no lo sea

En Building the most inaccessible site possible with a perfect Lighthouse score desarrollan un ejercicio muy interesante: cómo crear un sitio web que sea lo más inaccesible posible pero que obtenga una puntuación perfecta en una herramienta automática de evaluación de la accesibilidad.

lunes, 3 de junio de 2019

El símbolo universal de discapacidad

En Does the universal symbol for disability need to be rethought? se explica el origen del símbolo universal de discapacidad y se discute la necesidad de adecuarlo a la sociedad actual:

Ninety-three percent of people with disabilities don’t use a wheelchair, even though the universal symbol that identifies this group is a person in a wheelchair. Liam Riddler, a creative at London’s McCann office, points to his brother, who suffers from Crohn’s disease–a condition that causes inflammation of the digestive tract, potentially causing pain, severe diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, and malnutrition. It’s an invisible disability: Nobody would know about it by looking at him. Most people don’t understand why he may need to use accessible toilets or take advantage of priority seating.

Public ignorance of these invisible disabilities and the discrimination that results is what prompted Riddler and his colleague–McCann London’s deputy of art Lisa Carrana–to ask an obvious but difficult question: Do we need other symbols for people with invisible disabilities?

Riddler doesn’t claim to have an answer, but he and Carrana want to spur discussion around the issue with a project they have titled Visability93. Half provocation and half an effort to distill the graphical essence of these disabilities, the project is a crowdsourced competition that asks designers to submit their ideas about how to best graphically represent people with different invisible disabilities using individual symbols. So far they have 29 new icons (which you can download as a typeface here) that range from mental illnesses like anxiety, bipolar disorder, or depression, to physical conditions like asthma, arthritis, or diabetes. They’re using them in posters to raise awareness–and starting to imagine how they could potentially be applied in public to remind people that not all disabilities are visible.

viernes, 31 de mayo de 2019

La accesibilidad web también ayuda a las personas sin discapacidad

En el artículo Implementing Recommendations From Web Accessibility Guidelines: Would They Also Provide Benefits to Nondisabled Users se analizan las consecuencias de implementar las pautas de accesibilidad web para las personas sin discapacidad.

La conclusión fue que, en contra de lo que se suele pensar, un sitio web que cumpla las pautas de accesibilidad puede proporcionar beneficios a las personas sin discapacidad.

El resumen del artículo dice:

Objective:

We examined the consequences of implementing Web accessibility guidelines for nondisabled users.

Background:

Although there are Web accessibility guidelines for people with disabilities available, they are rarely used in practice, partly due to the fact that practitioners believe that such guidelines provide no benefits, or even have negative consequences, for nondisabled people, who represent the main user group of Web sites. Despite these concerns, there is a lack of empirical research on the effects of current Web accessibility guidelines on nondisabled users.

Method:

Sixty-one nondisabled participants used one of three Web sites differing in levels of accessibility (high, low, and very low). Accessibility levels were determined by following established Web accessibility guidelines (WCAG 2.0). A broad methodological approach was used, including performance measures (e.g., task completion time) and user ratings (e.g., perceived usability).

Results:

A high level of Web accessibility led to better performance (i.e., task completion time and task completion rate) than low or very low accessibility. Likewise, high Web accessibility improved user ratings (i.e., perceived usability, aesthetics, workload, and trustworthiness) compared to low or very low Web accessibility. There was no difference between the very low and low Web accessibility conditions for any of the outcome measures.

Conclusion:

Contrary to some concerns in the literature and among practitioners, high conformance with Web accessibility guidelines may provide benefits to users without disabilities.

Application:

The findings may encourage more practitioners to implement WCAG 2.0 for the benefit of users with disabilities and nondisabled users.

La conclusión fue que, en contra de lo que se suele pensar, un sitio web que cumpla las pautas de accesibilidad puede proporcionar beneficios a las personas sin discapacidad.

El resumen del artículo dice:

Objective:

We examined the consequences of implementing Web accessibility guidelines for nondisabled users.

Background:

Although there are Web accessibility guidelines for people with disabilities available, they are rarely used in practice, partly due to the fact that practitioners believe that such guidelines provide no benefits, or even have negative consequences, for nondisabled people, who represent the main user group of Web sites. Despite these concerns, there is a lack of empirical research on the effects of current Web accessibility guidelines on nondisabled users.

Method:

Sixty-one nondisabled participants used one of three Web sites differing in levels of accessibility (high, low, and very low). Accessibility levels were determined by following established Web accessibility guidelines (WCAG 2.0). A broad methodological approach was used, including performance measures (e.g., task completion time) and user ratings (e.g., perceived usability).

Results:

A high level of Web accessibility led to better performance (i.e., task completion time and task completion rate) than low or very low accessibility. Likewise, high Web accessibility improved user ratings (i.e., perceived usability, aesthetics, workload, and trustworthiness) compared to low or very low Web accessibility. There was no difference between the very low and low Web accessibility conditions for any of the outcome measures.

Conclusion:

Contrary to some concerns in the literature and among practitioners, high conformance with Web accessibility guidelines may provide benefits to users without disabilities.

Application:

The findings may encourage more practitioners to implement WCAG 2.0 for the benefit of users with disabilities and nondisabled users.

miércoles, 29 de mayo de 2019

lunes, 27 de mayo de 2019

Consulta sobre clase para hipoacúsicos

Hace unas semanas recibí la siguiente consulta:

Y mi respuesta:

No te puedo recomendar un software concreto, pero han surgido muchas opciones disponibles en Internet, además de la que nombras:

https://webcaptioner.com/

https://dictation.io/

https://speechnotes.co/es/

https://speechlogger.appspot.com/es/

https://talktyper.com/

https://www.speechtexter.com/

Y la extensión para Google Chrome:

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/voice-to-text/jdcdafhjjjfnkoeilnjmnadadaoehgdc

El micrófono es importante, pero quizás es mucho más importante la forma de hablar de la persona.

Te recomiendo que revises esta aplicación desarrollada en la Universidad de Alicante, quizás os pueda ayudar:

https://abilityconnect.ua.es/

Y también te recomiendo los siguientes recursos de la Universidad de Alicante sobre cómo afrontar la enseñanza de estudiantes con déficit auditivo:

Déficit auditivo. Accesibilidad Digital.

REGLAMENTO DE ADAPTACIÓN CURRICULAR DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE

ALICANTE

Adaptación curricular de la Universidad de Alicante: Caso II: Déficit Auditivo

Estimado Prof. Sergio Luján Mora, en nuestra facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Argentina, estamos implementado un política de accesibilidad en diversos ámbitos y me gustaría que me aconseje en el dictado de clases con alumnos con hipoacusia, pensé en pedirle al docente dictante que utilice un micrófono inalambrico conectado a una notebook conectada a internet y utilizar el Speechnotes o similar.

Las docentes de la cátedra suben la Bibliografía y el material de estudio al aula virtual con antelación a la clase.

El texto producto de lo que habla el docente se proyectaría en pantalla. Cúales serían sus consejos o recomendaciones acerca de:

a) modelo de micrófono:

b) software a utilzar, ¿ es bueno tener un software de pago como respaldo en caso de problemas de conexión con internet?, ¿cúal?

c) estragia didáctica:

espero su valiosa colaboración

saludos cordiales

Y mi respuesta:

No te puedo recomendar un software concreto, pero han surgido muchas opciones disponibles en Internet, además de la que nombras:

https://webcaptioner.com/

https://dictation.io/

https://speechnotes.co/es/

https://speechlogger.appspot.com/es/

https://talktyper.com/

https://www.speechtexter.com/

Y la extensión para Google Chrome:

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/voice-to-text/jdcdafhjjjfnkoeilnjmnadadaoehgdc

El micrófono es importante, pero quizás es mucho más importante la forma de hablar de la persona.

Te recomiendo que revises esta aplicación desarrollada en la Universidad de Alicante, quizás os pueda ayudar:

https://abilityconnect.ua.es/

Y también te recomiendo los siguientes recursos de la Universidad de Alicante sobre cómo afrontar la enseñanza de estudiantes con déficit auditivo:

Déficit auditivo. Accesibilidad Digital.

REGLAMENTO DE ADAPTACIÓN CURRICULAR DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE

ALICANTE

Adaptación curricular de la Universidad de Alicante: Caso II: Déficit Auditivo

viernes, 24 de mayo de 2019

La accesibilidad mal entendida

Las rampas que se pueden ver en las siguientes fotografías no sirven absolutamente para nada, no mejoran la accesibilidad.

En las páginas web muchas veces ocurre lo mismo, se implementan "rampas digitales" con el objetivo de mejorar la accesibilidad, "rampas digitales" que están mal hechas como las de las fotografías.

En las páginas web muchas veces ocurre lo mismo, se implementan "rampas digitales" con el objetivo de mejorar la accesibilidad, "rampas digitales" que están mal hechas como las de las fotografías.

miércoles, 22 de mayo de 2019

Las páginas de inicio todavía sobreviven

Las páginas de inicio, splash pages en inglés, fue una terrible epidemia que sufrió la Web a principios del siglo XXI.

Parecía que esta epidemia había sido erradicada, pero no.

En la Universidad Central del Ecuador le tienen cierta estima a las páginas de inicio:

Nada más llegar al sitio web, te plantan una imagen, con un montón de texto, que tapa el resto de la página web y que es difícil de leer porque es una imagen. Usabilidad, cero.

Pero no solo eso, para la accesibilidad es terrible, porque la imagen, claro está, no tiene un texto alternativo:

Y como se puede ver en la captura anterior, la imagen también tiene problemas para adaptarse al tamaño de visualización del dispositivo. Otra vez, usabilidad cero.

Parecía que esta epidemia había sido erradicada, pero no.

En la Universidad Central del Ecuador le tienen cierta estima a las páginas de inicio:

Nada más llegar al sitio web, te plantan una imagen, con un montón de texto, que tapa el resto de la página web y que es difícil de leer porque es una imagen. Usabilidad, cero.

Pero no solo eso, para la accesibilidad es terrible, porque la imagen, claro está, no tiene un texto alternativo:

Y como se puede ver en la captura anterior, la imagen también tiene problemas para adaptarse al tamaño de visualización del dispositivo. Otra vez, usabilidad cero.

lunes, 20 de mayo de 2019

Lo que pasa cuando se usa la Web todo un día solo con el teclado

En I Used The Web For A Day With Just A Keyboard:

SUMMARY

This experiment has been a mixed bag of great keyboard experiences and poor ones. I have three main takeaways.

KEEP IT STYLISH

By far the most common keyboard accessibility issue I’ve faced today is a lack of focus styling for tabbable elements. Suppressing native focus styles without defining any custom focus styles makes it extremely difficult, even impossible, to figure out where you are on the page. Removing the outline is such a common faux pas that there’s even a site dedicated to it.

Ensuring that native or custom focus styling is visible is the single most impactful thing you can do in the area of keyboard accessibility, and it’s often one of the easiest; a simple case of doubling up selectors on your existing :hover styling. If you only do one thing after reading this article, it should be to search for outline: 0 and outline: none in your CSS.

SEMANTICS ARE KEY

How many times have you tried opening a link in a new tab, only for your current window to get redirected? It happens to me every now and again, and annoying as it is, I’m lucky that it’s one of the only usability issues I tend to face when I use the web. Such issues arise from misusing the platform.

Let’s look at this code here:

<span onclick="window.location = 'https://google.com'">Click here</span>

Copy

An able, sighted user would be able to click on the <span> and be redirected to Google. However, because this is a <span> and not a link or a button, it doesn’t automatically have any focusability, so a keyboard or screen reader would have no way of interacting with it.

Keyboard-users are standards-reliant users, whereas the able, sighted demographic is privileged enough to be able to interact with the element despite its non-conformance.

Use the native features of the platform. Write good, clean HTML, and use validators such as https://validator.w3.org to catch things like missing href attributes on your anchors.

CONTENT IS KEY

You may be required to display cookie notices, subscription forms, adverts or adblock notices.

Do what you can to make these experiences unobtrusive. If you can’t make them unobtrusive, at least make them dismissible.

Users are there to see your content, not your banners, so put these dismissible elements first in your DOM so that they can be quickly dismissed, or fall back to using tabindex="1" if you can’t move them.

Finally, support your users in getting to your content as quickly as they can, by implementing the Holy Grail of ‘skip to main content’ links.

Stay tuned for the next article in the series, where I will be building upon some of these techniques when I use a screen reader for a day.

SUMMARY

This experiment has been a mixed bag of great keyboard experiences and poor ones. I have three main takeaways.

KEEP IT STYLISH

By far the most common keyboard accessibility issue I’ve faced today is a lack of focus styling for tabbable elements. Suppressing native focus styles without defining any custom focus styles makes it extremely difficult, even impossible, to figure out where you are on the page. Removing the outline is such a common faux pas that there’s even a site dedicated to it.

Ensuring that native or custom focus styling is visible is the single most impactful thing you can do in the area of keyboard accessibility, and it’s often one of the easiest; a simple case of doubling up selectors on your existing :hover styling. If you only do one thing after reading this article, it should be to search for outline: 0 and outline: none in your CSS.

SEMANTICS ARE KEY

How many times have you tried opening a link in a new tab, only for your current window to get redirected? It happens to me every now and again, and annoying as it is, I’m lucky that it’s one of the only usability issues I tend to face when I use the web. Such issues arise from misusing the platform.

Let’s look at this code here:

<span onclick="window.location = 'https://google.com'">Click here</span>

Copy

An able, sighted user would be able to click on the <span> and be redirected to Google. However, because this is a <span> and not a link or a button, it doesn’t automatically have any focusability, so a keyboard or screen reader would have no way of interacting with it.

Keyboard-users are standards-reliant users, whereas the able, sighted demographic is privileged enough to be able to interact with the element despite its non-conformance.

Use the native features of the platform. Write good, clean HTML, and use validators such as https://validator.w3.org to catch things like missing href attributes on your anchors.

CONTENT IS KEY

You may be required to display cookie notices, subscription forms, adverts or adblock notices.

Do what you can to make these experiences unobtrusive. If you can’t make them unobtrusive, at least make them dismissible.

Users are there to see your content, not your banners, so put these dismissible elements first in your DOM so that they can be quickly dismissed, or fall back to using tabindex="1" if you can’t move them.

Finally, support your users in getting to your content as quickly as they can, by implementing the Holy Grail of ‘skip to main content’ links.

Stay tuned for the next article in the series, where I will be building upon some of these techniques when I use a screen reader for a day.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)